Phydeaux

Posts: 4828

Joined: 1/4/2004

Status: offline

|

quote:

ORIGINAL: MasterJaguar01

quote:

ORIGINAL: Phydeaux

Unfortunately for you, you're wrong.

Were it a constitutional requirement for the Senate to act at the President's beck and call, the Justice department would be seeking a writ of mandamus faster than you can say, "well shit.".

However, since its not, and this is super well established... your opinion, frankly, is wrong.

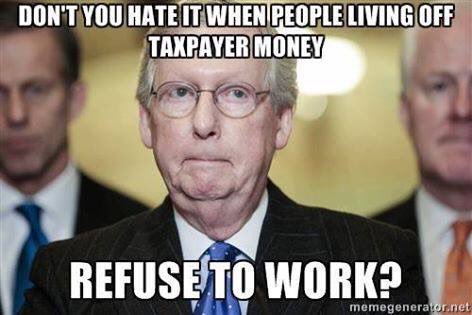

First of all, it wasn't supposed to work like that. It's supposed to be a government (all 3 branches) that may have its differences, but always put country over politics. There is supposed to be a generally known need to fill a vacancy, which will motivate the President and the Senate to act.

The President nominates, and (with advice and consent of the Senate) appoints someone to fill the vacancy. That is precisely the way it is worded in the Constitution (not my opinion. Just READ it!!!!) The vacancy itself is supposed to motivate our government to act. (As opposed to the Senate acting at the President's beck and call)

The premise of your argument is heavily flawed.

Secondly, as bounty so vigorously and irrelevantly pointed out, this kind of thing (unconstitutional behavior) happens all the time. No writ of mandamus.

So you are wrong on that point as well.

0 for 2 :(

No mate, your opinion is so wrong as to constitute stupid.

History lesson:

August 1828, Justice Robert Trimble died just as President John Quincy Adams was battling a tough reelection campaign against Democrat Andrew Jackson. Adams ended up losing to Jackson, but in December nominated Kentucky lawyer John Crittenden to replace Trimble. (Recall that before passage of the 20th Amendment in 1933, the presidential inauguration did not take place until March.)

Supporters of Jackson opposed this lame-duck nomination, leading to a debate of nine days on the floor of the Senate. Supporters of Adams’s maneuver argued that it was a duty of the president to fill vacant slots, even in the waning days of a presidency. They offered an amendment on the floor:

“That the duty of the Senate to confirm or reject the nominations of the President, is as imperative as his duty to nominate; that such has heretofore been the settled practice of the government; and that it is not now expedient or proper to alter it.”

But this amendment was rejected in a voice vote and then the Senate voted 23-17 to adopt an amendment saying “that it is not expedient to act upon the nomination of John I. Crittenden.” A few days after becoming president, Jackson nominated John McLean, the Postmaster General under Adams, to replace Trimble. (Jackson did this mainly to get McLean out of the Cabinet and to remove the possibility of him running for president, according to a study of the confirmation process.)

According to the Congressional Research Service, “By this action, the early Senate declined to endorse the principle that proper practice required it to consider and proceed to a final vote on every nomination.”

Or:

the case of Justice Henry Baldwin, who died in April 1844. That was also an election year, but the sitting president, John Tyler, was not running for reelection, having been expelled from the Whig Party during his presidency. So in effect, the Whig-controlled Senate was run by an opposition party.

Tyler made nine Supreme Court nominations during his presidency, but only one was approved. He made three nominations to fill Baldwin’s seat, all of which were rejected by the Senate until the new president, James Polk, took office. Polk was a Democrat, and even his first choice for the seat was rejected by the still-majority Whigs.

During the 1852 campaign between Democrat Franklin Pierce and Whig Winfield Scott, Justice John McKinley died in July. President Millard Fillmore, a Whig who was not running for reelection, nominated three candidates — one in August, one in January and one in February. The Democratic-controlled Senate took no action on two candidates and the third withdrew after the Senate postponed a vote until after inauguration. One of Fillmore’s nominations was never even considered by the Senate, while the other was simply tabled.

The fact that you can find any number of examples where the Senate acted promptly to confirm a nominee does not instill an obligation to do so.

|

Profile

Profile

New Messages

New Messages No New Messages

No New Messages Hot Topic w/ New Messages

Hot Topic w/ New Messages Hot Topic w/o New Messages

Hot Topic w/o New Messages Locked w/ New Messages

Locked w/ New Messages Locked w/o New Messages

Locked w/o New Messages Post New Thread

Post New Thread