Real0ne

Posts: 21189

Joined: 10/25/2004

Status: offline

|

quote:

ORIGINAL: FirmhandKY

Yeah, and what law says that?

Term,

The problem is that some people get caught up with the belief that the world is orderly, and must adhere to their particular point-by-point lawyerly legalese.

yes words are often minced over because in law every jot and jittle means something and conveys a peculiar and specific meaning

It doesn't.

"Laws" are nothing more and nothing less that what a society or group of societies claim, enforce, or adhere to.

or a dictator or a mob or the mafia

It doesn't matter if some cave-man lawyer back in the Pliocene, who was the chief law-maker of Ugg The All Ruler of the World (at the time) makes a "law" that everything in the Universe now belongs to Ugg forever and ever.

Did anyone every pass a law that specifically address it and made it invalid? Nope.

No that would eliminate the elite never happen

Same-same for most of Real0ne's stuff ... it simply doesn't matter in the "real world".

actually it does, one case below is from 1976

Most of the "legal" stuff he quotes (Magna Carta, anyone?) don't have "the force of law": [I beg to differ as you will soon see you are incorrect] they have a philosophical impact. The same can be said about English Common Law. [no] Why was it "common"? [it was common because it was not of the nobility and it was loval custom] Because it wasn't always written down, or "passed" by a legal act: it was "just the way things should be decided in the society". [that is not correct, the states converted common law to civil statotory by-law codification, in other words forcing round pegs in square holes philosophy, and most importantly to bring everything under their jurisdiction] It became the basis for many current laws, and for legal philosophical thinking. We inherited this "philosophy of justice". We didn't necessarily inherit the laws of Queen Elizabeth (or whoever). Semantics.

The Articles of Confederation weren't "legally superseded" [true] by an Act of Congress? Dunno. They were not. They were replaced in the real world, and everyone simply ignores them. That, by itself, is a definition of "superseded".

[should a case arise questioning the legitimacy or the creation of the states and there is reason to bring such a case to bear then you would see the articles of confederation front and center cited.]

Firm

Do you realize what you are "really" saying here?

A bunch of thugs come in and create a defacto guv because their guns are bigger and their lawyers are smarter and their pockets are bottomless pits because you are a tax payer and using their power to create a defacto MOBocracy on your back is not supposed to matter?

This country was "presumed" created by the "Rule of Law" not some bunch of thugs who come in and say this is the way it is going to be, [defacto] and then even worse the people saying [defacto] does not matter because that is the way it is?

How do you justify that any more than a big bully neighbor letting his dog dodo on your lawn then 50 years later the next property owner is supposed to say it does not matter?

quote:

Patrick Henry, June 4, 1788

I have the highest veneration for those gentlemen; but, sir, give me leave to demand, What right had they to say, We, the people?

My political curiosity, exclusive of my anxious solicitude for the public welfare, leads me to ask, Who authorized them to speak the language of, We, the people, instead of, We, the states? States are the characteristics and the soul of a confederation.

If the states be not the agents of this compact, it must be one great, consolidated, national government, of the people of all the states.

I have the highest respect for those gentlemen who formed the Convention, and, were some of them not here, I would express some testimonial of esteem for them. America had, on a former occasion, put the utmost confidence in them--a confidence which was well placed; and I am sure, sir, I would give up any thing to them; I would cheerfully confide in them as my representatives. But, sir, on this great occasion, I would demand the cause of their conduct. Even from that illustrious man who saved us by his valor [George Washington], I would have a reason for his conduct: that liberty which he has given us by his valor, tells me to ask this reason; and sure I am, were he here, he would give us that reason. But there are other gentlemen here, who can give us this information.

The people gave them no power to use their name. That they exceeded their power is perfectly clear.

SNIP

The federal Convention ought to have amended the old system; for this purpose they were solely delegated; the object of their mission extended to no other consideration.

---------------------------------------------

"A NATION-NOT A FEDERATION"

DELIVERED IN THE VIRGINIA CONVENTION ON THE EIGHTH SECTION OF THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTION

Mr. Chairman:

IT IS now confessed that this is a national government.

There is not a single federal feature in it.

It has been alleged, within these walls, during the debates, to be national and federal, as it suited the arguments of gentlemen.

The reasons adduced here to-day have long ago been advanced in favor of passive obedience and non-resistance. In 1688, the British nation expelled their monarch for attempting to trample on their liberties. The doctrine of Divine Right and Passive Obedience was said to be commanded by Heaven—it was inculcated by his minions and adherents. He wanted to possess, without control, the sword and purse. The attempt cost him his crown. This government demands the same powers. I see reason to be more and more alarmed. I fear it will terminate in despotism. As to his objection of the abuse of liberty, it is denied. The political inquiries and promotions of the peasants are a happy circumstance. A foundation of knowledge is a great mark of happiness.

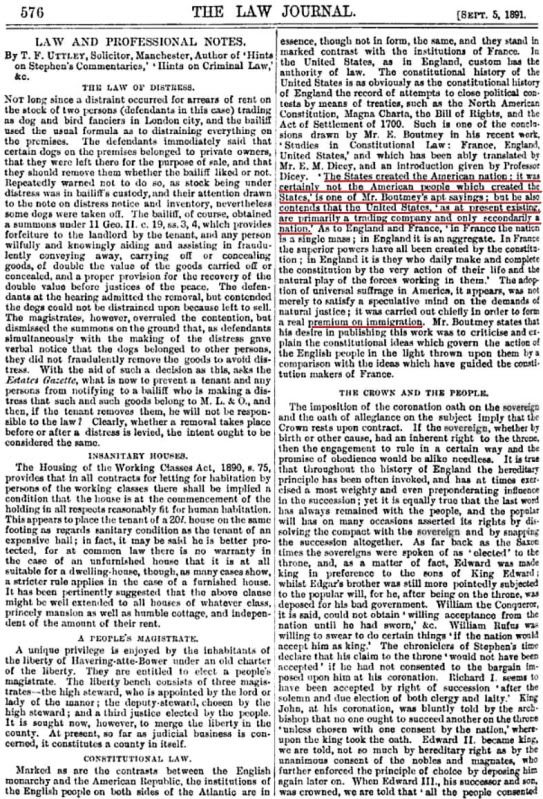

quote:

Klopfer v. North Carolina, 386 US 213

We hold here that the right to a speedy trial is as fundamental as any of the rights secured by the Sixth Amendment. That right has its roots at the very foundation of our English law heritage. Its first articulation in modern jurisprudence appears to have been made in Magna Carta (1215), wherein it was written, "We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either justice or right";[8] but evidence of recognition of the right to speedy justice in even earlier times is found in the Assize of Clarendon (1166).[9] By the late thirteenth century, justices, armed with commissions of gaol delivery and/or oyer and terminer[10] were visiting the 224*224 countryside three times a year.[11]

These justices, Sir Edward Coke wrote in Part II of his Institutes, "have not suffered the prisoner to be long detained, but at their next coming have given the prisoner full and speedy justice, . . . without detaining him long in prison."[12] To Coke, prolonged detention without trial would have been contrary to the law and custom of England;[13] but he also believed that the delay in trial, by itself, would be an improper denial of justice. In his explication of Chapter 29 of the Magna Carta, he wrote that the words "We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either justice or right" had the following effect:

"And therefore, every subject of this realme, for injury done to him in bonis, terris, vel persona, by any other subject, be he ecclesiasticall, or temporall, free, or bond, man, or woman, old, or young, or be he outlawed, excommunicated, or any other without exception, may take his remedy by the course of the law, and have justice, and right for the injury done to him, freely without sale, fully without any deniall, and speedily without delay."[14]

225*225 Coke's Institutes were read in the American Colonies by virtually every student of the law.[15] Indeed, Thomas Jefferson wrote that at the time he studied law (1762-1767), "Coke Lyttleton was the universal elementary book of law students."[16] And to John Rutledge of South Carolina, the Institutes seemed "to be almost the foundation of our law."[17] To Coke, in turn, Magna Carta was one of the fundamental bases of English liberty.[18] Thus, it is not surprising that when George Mason drafted the first of the colonial bills of rights,[19] he set forth a principle of Magna Carta, using phraseology similar to that of Coke's explication: "n all capital or criminal prosecutions," the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776 provided, "a man hath a right . . . to a speedy trial . . . ."[20] That this right was considered fundamental at this early period in our history is evidenced by its guarantee in the constitutions of several of the States of the new nation,[21] 226*226 as well as by its prominent position in the Sixth Amendment. Today, each of the 50 States guarantees the right to a speedy trial to its citizens.

The history of the right to a speedy trial and its reception in this country clearly establish that it is one of the most basic rights preserved by our Constitution.

For the reasons stated above, the judgment must be reversed and remanded for proceedings not inconsistent with the opinion of the Court.

It is so ordered.

MR. JUSTICE STEWART concurs in the result.

MR. JUSTICE HARLAN, concurring in the result.

quote:

Hurtado v. California, 110 US 516

The question is one of grave and serious import, affecting both private and public rights and interests of great magnitude, and involves a consideration of what additional restrictions upon the legislative policy of the States has been imposed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

The Supreme Court of California, in the judgment now under review, followed its own previous decision in Kalloch v. Superior Court, 56 Cal. 229, in which the question was deliberately adjudged. Its conclusion was there stated as follows:

"This proceeding, as [it] is regulated by the Constitution and laws of this State, is not opposed to any of the definitions given of the phrases `due process of law' and `the law of the land;' but, on the contrary, it is a proceeding strictly within such definitions, as much so in every respect as is a proceeding by indictment. It may be questioned whether the proceeding by indictment secures to the accused any superior rights and privileges; but certainly a prosecution by information takes from him no immunity or protection to which he is entitled under the law."

And the opinion cites and relies upon a decision of the Supreme Court of Wisconsin in the case of Rowan v. The State, 30 Wis. 129. In that case the court, speaking of the Fourteenth Amendment, says:

"But its design was not to confine the States to a particular mode of procedure in judicial proceedings, and prohibit them from 521*521 prosecuting for felonies by information instead of by indictment, if they chose to abolish the grand jury system. And the words `due process of law' in the amendment do not mean and have not the effect to limit the powers of State governments to prosecutions for crime by indictment; but these words do mean law in its regular course of administration, according to prescribed forms, and in accordance with the general rules for the protection of individual rights. Administration and remedial proceedings must change, from time to time, with the advancement of legal science and the progress of society; and, if the people of the State find it wise and expedient to abolish the grand jury and prosecute all crimes by information, there is nothing in our State Constitution and nothing in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States which prevents them from doing so."

[typical wisconsin backwards logic, there is nothing that authorizes them to do so]

On the other hand, it is maintained on behalf of the plaintiff in error that the phrase "due process of law" is equivalent to "law of the land," as found in the 29th chapter of Magna Charta; that by immemorial usage it has acquired a fixed, definite, and technical meaning; that it refers to and includes, not only the general principles of public liberty and private right, which lie at the foundation of all free government, but the very institutions which, venerable by time and custom, have been tried by experience and found fit and necessary for the preservation of those principles, and which, having been the birthright and inheritance of every English subject, crossed the Atlantic with the colonists and were transplanted and established in the fundamental laws of the State; that, having been originally introduced into the Constitution of the United States as a limitation upon the powers of the government, brought into being by that instrument, it has now been added as an additional security to the individual against oppression by the States themselves; that one of these institutions is that of the grand jury, an indictment or presentment by which against the accused in cases of alleged felonies is an essential part of due process of law, in order that he may not be harassed or destroyed by prosecutions founded only upon private malice or popular fury.

This view is certainly supported by the authority of the 522*522 great name of Chief Justice Shaw and of the court in which he presided, which, in Jones v. Robbins, 8 Gray, 329, decided that the 12th article of the Bill of Rights of Massachusetts, a transcript of Magna Charta in this respect, made an indictment or presentment of a grand jury essential to the validity of a conviction in cases of prosecutions for felonies. In delivering the opinion of the court in that case, Merrick, J., alone dissenting, the Chief Justice said:

"The right of individual citizens to be secure from an open and public accusation of crime, and from the trouble, expense, and anxiety of a public trial before a probable cause is established by the presentment and indictment of a grand jury, in case of high offences, is justly regarded as one of the securities to the innocent against hasty, malicious, and oppressive public prosecutions, and as one of the ancient immunities and privileges of English liberty."

... "It having been stated," he continued, "by Lord Coke, that by the `law of the land' was intended a due course of proceeding according to the established rules and practice of the courts of common law, it may, perhaps, be suggested that this might include other modes of proceeding sanctioned by the common law, the most familiar of which are, by informations of various kinds, by the officers of the crown in the name of the King. But, in reply to this, it may be said that Lord Coke himself explains his own meaning by saying `the law of the land,' as expressed in Magna Charta, was intended due process of law, that is, by indictment or presentment of good and lawful men. And further, it is stated, on the authority of Blackstone, that informations of every kind are confined by the constitutional law to misdemeanors only. 4 Bl. Com. 310."

Referring again to the passage from Lord Coke, he says, p. 343:

"This may not be conclusive, but, being a construction adopted by a writer of high authority before the emigration of our ancestors, it has a tendency to show how it was then understood."

This passage from Coke seems to be the chief foundation of the opinion for which it is cited; but a critical examination and 523*523 comparison of the text and context will show that it has been misunderstood; that it was not intended to assert that an indictment or presentment of a grand jury was essential to the idea of due process of law in the prosecution and punishment of crimes, but was only mentioned as an example and illustration of due process of law as it actually existed in cases in which it was customarily used. In beginning his commentary on this chapter of Magna Charta, 2 Inst. 46, Coke says:

"This chapter containeth nine several oranches:

"1. That no man be taken or imprisoned but per legem terræ, that is, by the common law, statute law, or custom of England; for the words per legem terræ, being towards the end of this chapter, doe referre to all the precedent matters in the chapter, etc.

"2. No man shall be disseised, etc., unless it be by the lawful judgment, that is, verdict of his equals, (that is of men of his own condition,) or by the law of the land, (that is to speak it once for all,) by the due course and process of law."

He then proceeds to state that, 3, no man shall be outlawed, unless according to the law of the land; 4, no man shall be exiled, unless according to the law of the land; 5, no man shall be in any sort destroyed, "unlesse it be by the verdict of his equals, or according to the law of the land;" 6, "no man shall be condemned at the King's suite, either before the King in his bench, where the pleas are coram rege, (and so are the words nec super eum ibimus to be understood,) nor before any other commissioner or judge whatsoever, and so are the words nec super eum mittemus to be understood, but by the judgment of his peers, that is, equals, or according to the law of the land."

Recurring to the first clause of the chapter, he continues:

"1. No man shall be taken (that is) restrained of liberty by petition or suggestion to the King or to his councill, unless it be by indictment or presentment of good and lawfull men, where such deeds be done. This branch and divers other parts of this act have been notably explained by divers acts of Parliament, &c., quoted in the margent."

The reference is to various acts during the reign of Edward 524*524 III. And reaching again the words "nisi per legem terræ," he continues:

"But by the law of the land. For the true sense and exposition of these words see the statute of 37 E. 3, cap. 8, where the words, by the law of the land, are rendered, without due proces of the law, for there it is said, though it be contained in the Great Charter, that no man be taken, imprisoned, or put out of his freehold without proces of the law, that is, by indictment of good and lawfull men, where such deeds be done in due manner, or by writ originall of the common law. Without being brought in to answere but by due proces of the common law. No man be put to answer without presentment before justices, or thing of record, or by due proces, or by writ originall, according to the old law of the land. Wherein it is to be observed that this chapter is but declaratory of the old law of England."

It is quite apparent from these extracts that the interpretation usually put upon Lord Coke's statement is too large, because if an indictment or presentment by a grand jury is essential to due process of law in all cases of imprisonment for crime, it applies not only to felonies but to misdemeanors and petty offences, and the conclusion would be inevitable that informations as a substitute for indictments would be illegal in all cases. It was indeed so argued by Sir Francis Winninton in Mr. Prynn's Case, 5 Mod. 459, from this very language of Magna Charta, that all suits of the King must be by presentment or indictment, and he cited Lord Coke as authority to that effect. He attempted to show that informations had their origin in the act of 11 Hen. 7, c. 3, enacted in 1494, known as the infamous Empson and Dudley act, which was repealed by that of 1 Hen. 8, c. 6, in 1509. But the argument was overruled, Lord Holt saying that to hold otherwise "would be a reflection on the whole bar." Sir Bartholomew Shower, who was prevented from arguing in support of the information, prints his intended argument in his report of the case under the name of The King v. Berchet, 1 Show. 106, in which, with great thoroughness, he arrays all the learning of the time on the subject. He undertakes to "evince that this method of prosecution is noways contrariant 525*525 to any fundamental rule of law, but agreeable to it." He answers the objection that it is inconvenient and vexatious to the subject by saying (p. 117):

"Here is no inconvenience to the people. Here is a trial per pais, fair notice, liberty of pleading dilatories as well as bars. Here is subpœna and attachment, as much time for defence, charge, &c., for the prosecutor makes up the record, &c.; then, in case of malicious prosecution, the person who prosecutes is known by the note to the coroner, according to the practice of the court."

He answers the argument drawn from Magna Charta, and says:

"That this method of prosecution no way contradicts that law, for we say this is per legem terræ et per communem legem terræ, for otherwise there never had been so universal a practice of it in all ages."

And referring to Coke's comment, that "no man shall be taken," i.e., restrained of liberty by petition or suggestion to the King or his Council unless it be by indictment or presentment, he says (p. 122):

and on and on and on

so if the magna charta has no force in law then you need to explain why in the world the supreme court would be citing it along with blackstone and coke ett al? Hmmmmm?

< Message edited by Real0ne -- 8/28/2011 8:25:56 PM >

_____________________________

"We the Borg" of the us imperialists....resistance is futile

Democracy; The 'People' voted on 'which' amendment?

Yesterdays tinfoil is today's reality!

"No man's life, liberty, or property is safe while the legislature is in session

|

Profile

Profile

New Messages

New Messages No New Messages

No New Messages Hot Topic w/ New Messages

Hot Topic w/ New Messages Hot Topic w/o New Messages

Hot Topic w/o New Messages Locked w/ New Messages

Locked w/ New Messages Locked w/o New Messages

Locked w/o New Messages Post New Thread

Post New Thread